industrialization & immigration

The Great Migration

Following the end of Reconstruction in 1876, and because of deeply ingrained hostility towards the idea of African-American equality, a system of enforced racial segregation was implemented across the southern U.S. Named for a cartoon character that embodied black stereotypes, the Jim Crow system reinforced local sentiments of white superiority and served as a means of controlling the African-American population. Former slaves and their descendants were forbidden from entering certain business establishments and public facilities, excluded from certain parts of town, and largely confined to work as sharecroppers burdened by perpetual debt. Despite the language of the Fourteenth Amendment making the former slaves citizens and calling for equal protection, poll taxes and grandfather clauses were used to prevent blacks from voting. Racial segregation was enforced by intimidation and violence through harassment, lynching, and terrorism by the Ku Klux Klan. The Jim Crow system effectively denied African-Americans political and legal equality and limited access to education and employment opportunities that could improve life for the black population in the South.

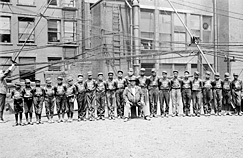

As a result, an exodus of African-Americans out of the South began soon after the turn of the century. Though many African-Americans left the South hoping to escape racism, they encountered it in the North as well, even in supposedly progressive places like Springfield and Holyoke. In both cities, there was an unofficial color line that prevented African-Americans from easily obtaining housing outside of certain proscribed areas-Wards 1 and 2 in Holyoke and the Willow and Cross streets area of Springfield. African-Americans were also repressed in the workplace. Most employers would only hire African-Americans for low-paying, low-skill jobs such as janitors, house cleaners, chauffeurs, and hotel-workers, though by the 1930's a small number of African-Americans were working as machinists, masons, tailors, barbers, and carpenters. Increased production at the Springfield Armory during World War II expanded opportunities for black workers, and many developed the confidence and skills necessary to secure steady employment after the war. Education and rising wages remained the key to upward social mobility, but poor schools and the expense of higher education limited opportunities for most African-Americans. Still, a significant number managed to earn college degrees, becoming writers, teachers, ministers, doctors, dentists, and lawyers and joining a small but growing black middle class.

As the African-American population of the Connecticut River Valley grew, new organizations emerged to promote racial equality and improved opportunities in education and employment. In 1913, Dr. John N. DeBerry, minister of St. John's Church in Springfield, began the Dunbar Community League (now called the Urban League of Springfield), which grew to include homes for boys and girls, a youth club, adult educational programs, a low income housing project, and Camp Atwater, which is today the oldest African-American owned and operated summer residential youth camp in the nation. Progress toward improvements in civil rights also came with the formation of local chapters of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) in both Springfield and Holyoke. In the 1920s, Holyoke's NAACP branch successfully sued barber John Hall for refusing to serve African-Americans. These early civil rights organizations would form the foundation of the movement for equal rights that began to gather steam across the nation in the mid-1950s.